Most of us who have followed a story felt attachment to the main characters. Maybe you yelled at the puppet show as a kid to warn them of the character in the dark who was about to knock, or you revelled in the danger and you felt a little empty after the story was over. Such feelings of attachment can be even stronger when you take up the role of the character, that is, to become the one who knocks, or jumps, or solves puzzles, and saves the dragon. Yes, kids, save the dragon. Rescuing the damsel in distress is so yesteryear.

The avatars we play may not be us. But in some games we get a lot of options to tune the avatar to our liking, and perhaps play a bit with our own understanding of our identity. They may look better, behave far better, or act as indiscriminate rogues, and you may think of them as more dateable than you are. Despite differences between the virtual world and real life (here on earth dragons are merely some sunbathing lizards), in-game experiences can transfer beyond the fantasy realm into everyday life and contribute to our understanding of ourselves. This touches upon our project interests, because we do have memories of those experiences.

In fact, those memories pop up in everyday life. A recent study by Poels, IJsselsteijn, and de Kort (2014) surveyed players of the online role-playing game World of Warcraft to see in what way the game influenced the thinking and dreaming of frequent players. They indeed found evidence for elements of the game to play a role in daydreaming and mundane thoughts. Additionally, their results indicated that objects in normal life may remind people of their virtual exploits. Unfortunately no examples of such objects and thoughts were included. It would have been interesting to see how real things relate to experiences in another realm. We do not need to wear our ‘Epic Hat of Uncertain Principles’ to reminisce about experiences we had while wearing that hat.

Three years ago I started to take screenshots of a game I was playing at the time, the role-playing fantasy game Skyrim. I thought it strange that we do photograph a day trip to a theme park, but not keep evidence of the countless hours we spend in an elaborate fantasy world. Perhaps we are too busy just being entertained by the game, or perhaps it is a social stigma to not show those unfettered glimpses into what we really prefer for enjoyment. After all, there is something of us in the choices we made for an avatar, even if it’s just to explore an alter ego. For example, a fairly large proportion of men play as female characters and certainly not always in skimpy, revealing outfits as you may expect. Similar experimenting happens the other way around as well. Maybe it is exactly this playing with identity that keeps it separate from our idea of who we are, and therefore any screenshots do not end up in a visual narrative of our life.

Yet, here I am writing this because I did take some screenshots that ended up alongside my other, personal pictures. Looking over my photos, there was no distinction between my life and that of my game characters.

One of the screenshots I took more than a year ago. Yes, that is my beloved character named Cruela with whom I spent somewhere close to 270 hours in-game. Make of that what you will.

One of the screenshots I took more than a year ago. Yes, that is my beloved character named Cruela with whom I spent somewhere close to 270 hours in-game. Make of that what you will.

This leaves me with a few questions. Do people capture any visual material from in-game experiences? Do they construct a narrative to go along with it? To what extent does that story relate to their real lives? Do they ever look back? If they do look back, is it ever shared with others? I wonder. For a games industry that builds on giving us enjoyable experiences, obtainable achievements, and in MMO’s also some amount of social status, seemingly little flows over into our everyday lives when it comes to remembering all those things.

While the actual gaming experience and avatars used to attain those are perhaps under-represented in the publicly observable realm of memory-supporting media, cosplay has seen quite a bit of popularity in the past decades. Cosplay, or dressing up as your favourite game, comic, movie, or series hero, is a way of expressing fandom through often elaborate self-made costumes. Even though doing so does not express the personal experiences of playing a game or watching fiction, it does indicate the cosplayer was in some way infatuated with that piece of popular culture and not afraid to show it.

Looking into personal memories of gaming and other forms of fandom provides a nice bridge between media studies and the study of everyday remembering. Would you be willing to share your stories? And do you consider those part of your personal past?

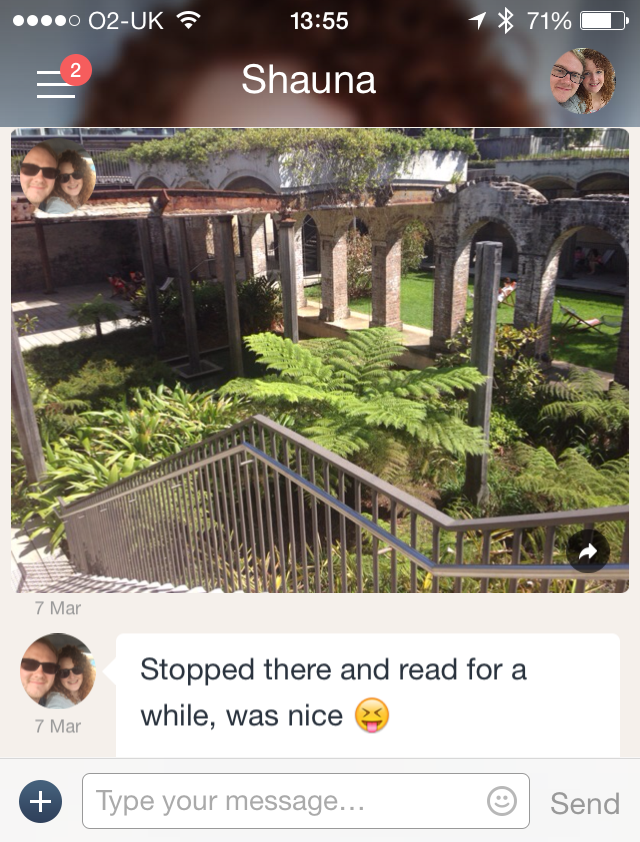

On 22 March the Materialising Memories team (and some MM friends) left their offices to embark on their fifth Making Memories Day. Our team outing started in the afternoon in The Rocks, the oldest part of Sydney, for an Urban Hunt (interactive scavenger hunt). We split up in two teams and via an interactive Messenger chat we received questions and cryptic clues. By following these cryptic walking directions and searching for the right answers, we passed small alleys and historical places and facts in The Rocks we had never seen or known before.

On 22 March the Materialising Memories team (and some MM friends) left their offices to embark on their fifth Making Memories Day. Our team outing started in the afternoon in The Rocks, the oldest part of Sydney, for an Urban Hunt (interactive scavenger hunt). We split up in two teams and via an interactive Messenger chat we received questions and cryptic clues. By following these cryptic walking directions and searching for the right answers, we passed small alleys and historical places and facts in The Rocks we had never seen or known before. After a short Ferry and Light Rail ride we arrived at our dinner place, The Tramsheds. Some more team members joined us here who were not able to attend our afternoon activity. We enjoyed our dinner in a restored Sydney tram.

After a short Ferry and Light Rail ride we arrived at our dinner place, The Tramsheds. Some more team members joined us here who were not able to attend our afternoon activity. We enjoyed our dinner in a restored Sydney tram.